Lab 7: Trees and Recursion

Learning outcomes

By the end of this lab, you will be able to:

- Write recursive methods to perform non-mutating and mutating tasks on trees.

- Augment a tree data structure (add a new attribute) to improve the efficiency of one or more tree operations.

- Use the pygame library to create a simple graphical program

- Apply recursive thinking to a new geometric domain

Task 0: Setup and review

Download tree.py, and tiling.py

into the labs/lab7 folder.

Review

Recall that we have introduced a new data structure, the Tree. We often use trees to represent

data which falls naturally into a hierarchical, non-linear structure (like a family tree or corporate

hierarchy), and we will soon see an application of trees to efficiently storing ordered data.

In Python, we implement a tree using a class with two private attributes, _root and

_subtrees, which represent the value at the root of the tree and the list of subtrees of that

tree, respectively. Since the subtrees are themselves trees, we call trees a recursive data structure: it is

built out of parts which have the same structure as the whole. This is reflected in our code: we tend to

compute on trees using recursive functions and methods, whose code tends to follow the same structure as the

tree itself:

def my_tree_method(self) -> ...:

if self.is_empty():

...

else:

...

for subtree in self._subtrees:

... subtree.my_tree_method() ...

...Of course, the hard work is figuring out how to fill in and modify this template to get the desired behaviour. But keep this code pattern in mind as you work through the lab exercises.

Get some paper!

Before starting the exercises, make sure you do the following. Trust us, it will make reasoning about your code much easier later on.

Take a blank sheet of paper, and draw the following three trees:

- An empty tree (just write the word “Empty” or something similar).

- A tree with just one value.

- A tree with at least three subtrees, which each have height >= 3. Draw triangles around each of the subtrees.

Task 1: Non-mutating tree methods

Branching Factors

Consider the following definition. The branching factor of an item in a tree is its number of children (or equivalently, its number of subtrees). In Artificial Intelligence, one of the most important properties of a tree is the average branching factor of its internal values (i.e., of its non-leaf values).

Your first task is to implement the method Tree.branching_factor that computes the

average branching factor of the internal nodes in a tree. The average branching factor is

calculated as the average of all branching factors of internal (non-leaf) nodes.

Hint: similar to the method Tree.average we covered in lecture, it’s not enough simply

to recursively compute the average branching factor of each subtree. Instead, you and your partner should

write a recursive helper method that returns two values that together can be used to compute this average

branching factor, and where the values can be computed recursively.

Items at depth

The depth of an item in a tree is the distance (counting values) between the item and the root of the tree, inclusive. So the root of the tree has depth 1, its children have depth 2, the children of its children have depth 3, etc.

Before jumping right to the code, practice thinking recursively by doing the following:

- If you haven’t done so already, draw a tree of height 4 that has at least three subtrees.

- Circle all of the items in your tree at depth 3.

- Redraw each subtree of your tree separately (leave space between them).

- On each subtree, circle the same items that you circles in step 2.

- What is the depth of the items you circled, relative to the subtree (hint: it’s not depth 3)?

After you’ve answered the last part, you’re ready to implement Tree.items_at_depth!

Task 2: A mutating method (insert)

Here, we’re going to study some tree mutation: inserting a value into a tree. To avoid disrupting the structure of the tree, we’re going to move down the tree until we reach an “empty spot” and then create a new leaf there.

The way that we’ve defined trees, we can add a new leaf at any spot in the tree (simply append a new subtree

to a _subtrees list). To make things a bit more interesting, you’re going to explore Python’s

built-in random module to generate random choices as you go down the tree.

Implement the Tree.insert method by following the algorithm in its docstring.

Task 3: Augmenting the Tree

As we saw with linked lists a few weeks ago, our current implementation of Tree.__len__ is

rather inefficient: it must recalculate the size of each subtree (recursively) every time it is called.

Your final task in this lab is to augment your Tree class by adding a new

size instance attribute that represents the size of a tree. You might be tempted to jump right

to using it in Tree.__len__, but remember that every new attribute we add must be taken into

account in the implementations for the initializer and every mutating method!

- For the initializer, you receive a list of

Trees as input. You should assume that their size attributes are set properly, and simply use each input subtree’s size to initializeself.size. - For the insertion and deletion algorithms you developed in lecture and this lab, make sure to update

self.sizewhen an item is inserted/removed.

You might be nervous about modifying your existing Tree class implementation. If you do this

task properly, you shouldn’t have to delete any of the existing code you wrote, but instead add new code to

a few methods to keep the size attribute up to date!

Additional exercise: Pygame and a different kind of recursion

Although this is an additional exercise, we encourage you to complete it (after lab if necessary), because it

explores a rather different use of recursion than what you’ve seen before and will also help you become more

familiar with the pygame Python library for displaying graphics in Python. We’ll use pygame

more in Assignment 2.

Open up tiling.py and skip down to the main block. It does two things: calls

draw_grid(5), and then waits for user input. Try running this file—you should see a new window

appear. Cool!

To exit, press Enter in the Run console in PyCharm (note that you won’t be able to close the window by pressing the X like you would expect).

Take a minute or two to read the draw_grid function. We’ve provided all the code necessary to

draw a picture in pygame; the most important function to understand for later assignment work is

pygame.draw.rect, which you can read about in more detail here.

Tiling

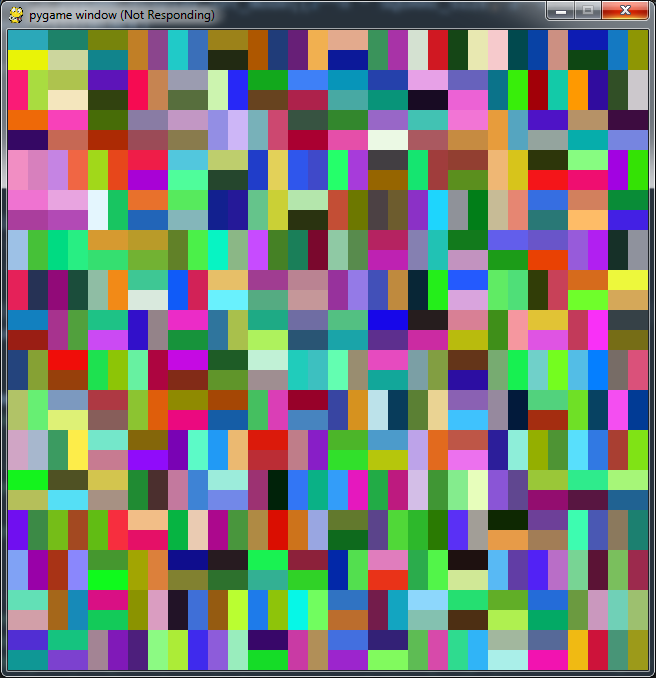

Your goal for this task is to randomly tile the grid using dominoes, producing a pygame window that looks like this:

A domino is a 1-by-2 rectangle (so it takes up two squares on the grid). We tile a grid by filling it with dominoes so that no two dominoes overlap, and all grid squares are covered.

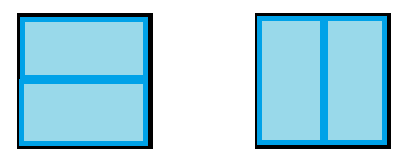

For example, there are two ways to tile a 2-by-2 grid using dominoes, laying them horizontally or vertically:

What about larger grids? When the grid size is 2^n by 2^n (n > 1), we can tile this using recursion:

- Break it up into four quadrants, each of size 2^(n-1) by 2^(n-1).

- Recursively tile each quadrant.

Even though this really is a recursive approach, it may feel different from all the work we’ve done on recursion so far. That’s because the recursive structure of the input isn’t as obvious as that of nested lists or trees. We really have to understand that to tile a grid of size 2^n by 2^n, we can break up this grid into four parts of smaller size, and tile each one separately!

Implementing recursive domino tiling

Your task is to take your understanding of the recursive tiling approach in the previous section and

implement it in tiling.py.

- Read the docstrings for the

Dominoclass. Note that we have implemented this class for you already, and you shouldn’t change it (or even read the code) to do this lab. - Read the docstring of

tile_with_dominoes. This is the main recursive function you’ll be working on. This function must return a list of Domino objects representing a complete tiling of a 2^n by 2^n grid. Note that we’ve prepared some of the structure of this code for you. - Implement the base case helper function

_tile_2_by_2. You may wish to review the previous description of tiling here. - Uncomment the block in

draw_grid, and change the function call in the main block todraw_grid(1). This will let you test out the base case of your function. Don’t move on until this part works! - Implement the recursive step. We’ve given you some more hints in the code to do this.

- Try calling

draw_gridon a number greater than 1, and see what happens!